A Foundation Model for Sleep-Based Risk Stratification and Clinical Outcomes

We are thrilled to share that our latest research, "A Foundation Model for Sleep-Based Risk Stratification and Clinical Outcomes," has been accepted for publication in Nature Communications. This work represents a significant leap forward in precision sleep medicine, moving us past decades of reliance on narrow metrics to a future defined by comprehensive, AI-driven physiologic insights. The study was conducted in close collaboration with clinical sleep experts and neuroscientists from Cleveland Clinic and the University of Washington, ensuring that the modeling choices, physiologic interpretations, and clinical validations were grounded in real-world sleep medicine practice and neuroscience expertise.

While this research was conducted during my tenure at IBM Research, its central idea—using foundation models to extract actionable structure from complex, high-dimensional data—closely aligns with the work we are now pursuing at Hogarthian Technologies.

At Hogarthian, we are focused on building intelligent voice agents that can operate reliably in real-world environments, starting with handling restaurant calls and conducting patient surveys. The broader lesson from this research—that single metrics and brittle heuristics fail in complex systems—directly informs how we design and scale these agents.

The Problem: The "AHI Ceiling"

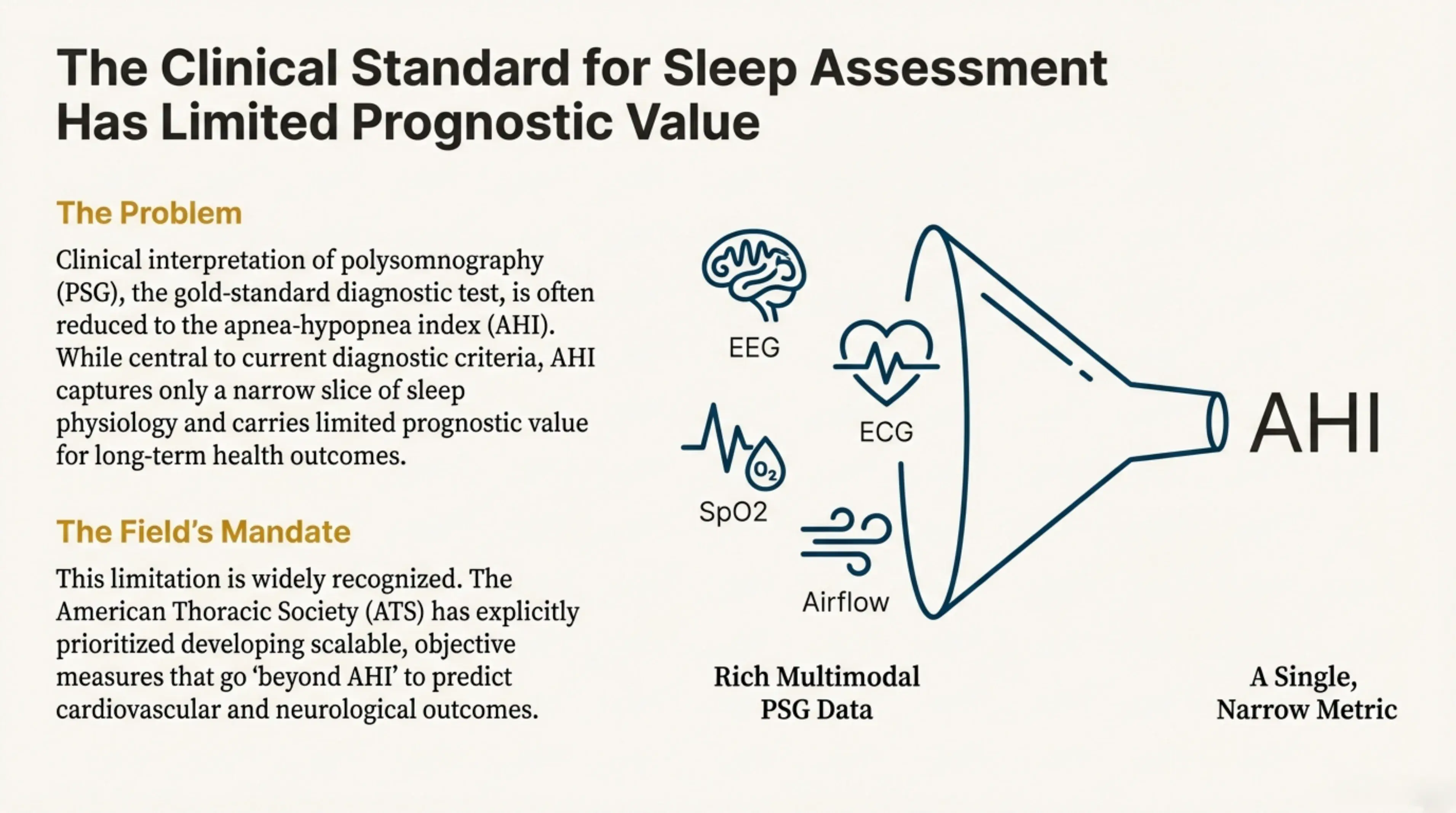

For years, the gold standard for diagnosing sleep disorders has been the Apnea–Hypopnea Index (AHI). AHI is derived from Polysomnography (PSG)—an overnight sleep study that records multiple physiological signals, including brain activity (EEG), heart rhythms (ECG), blood oxygen levels (SpO₂), airflow, and respiratory effort.

Despite the richness of these recordings, clinical interpretation is often reduced to a single number. AHI counts the frequency of breathing interruptions but does not reflect the broader structure of sleep physiology or the interactions between neural, cardiac, and respiratory systems.

In clinical practice, the interpretation of polysomnography often functions like a funnel: high-dimensional, multimodal PSG signals enter on one side, and a single summary metric—AHI—emerges on the other. This compression discards much of the physiological information present in the original recordings, limiting the ability of AHI alone to capture meaningful differences in long-term health risk.

Clinical interpretation of polysomnography is often reduced to the AHI, a single narrow metric. Rich multimodal PSG data (EEG, ECG, SpO2, airflow) gets compressed into one number that carries limited prognostic value for long-term health outcomes.

Clinical interpretation of polysomnography is often reduced to the AHI, a single narrow metric. Rich multimodal PSG data (EEG, ECG, SpO2, airflow) gets compressed into one number that carries limited prognostic value for long-term health outcomes.

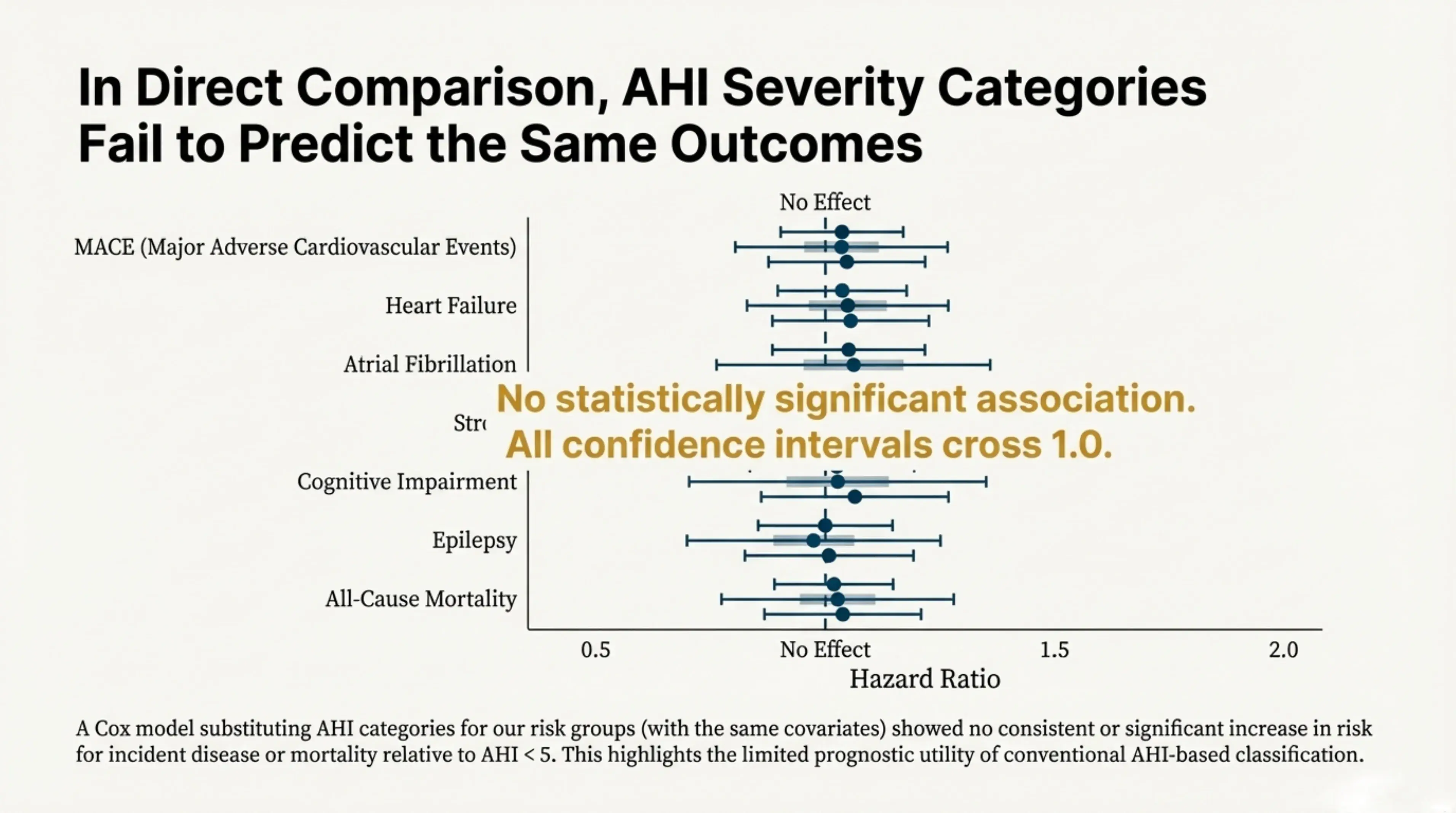

Our study confirmed a sobering reality: AHI severity categories often fail to predict long-term mortality or the incidence of cardiovascular and neurological diseases. When patients are stratified using standard AHI cutoffs (mild, moderate, severe), these categories show no consistent association with survival or major adverse cardiovascular events. Across outcomes, the estimated effects cluster around null, indicating little to no prognostic signal.

In direct comparison, AHI severity categories fail to predict the same outcomes. This plot illustrates how AHI categories provide almost no predictive signal for mortality, highlighting the urgent need for better biomarkers.

In direct comparison, AHI severity categories fail to predict the same outcomes. This plot illustrates how AHI categories provide almost no predictive signal for mortality, highlighting the urgent need for better biomarkers.

The Solution: A Foundation Model for Sleep

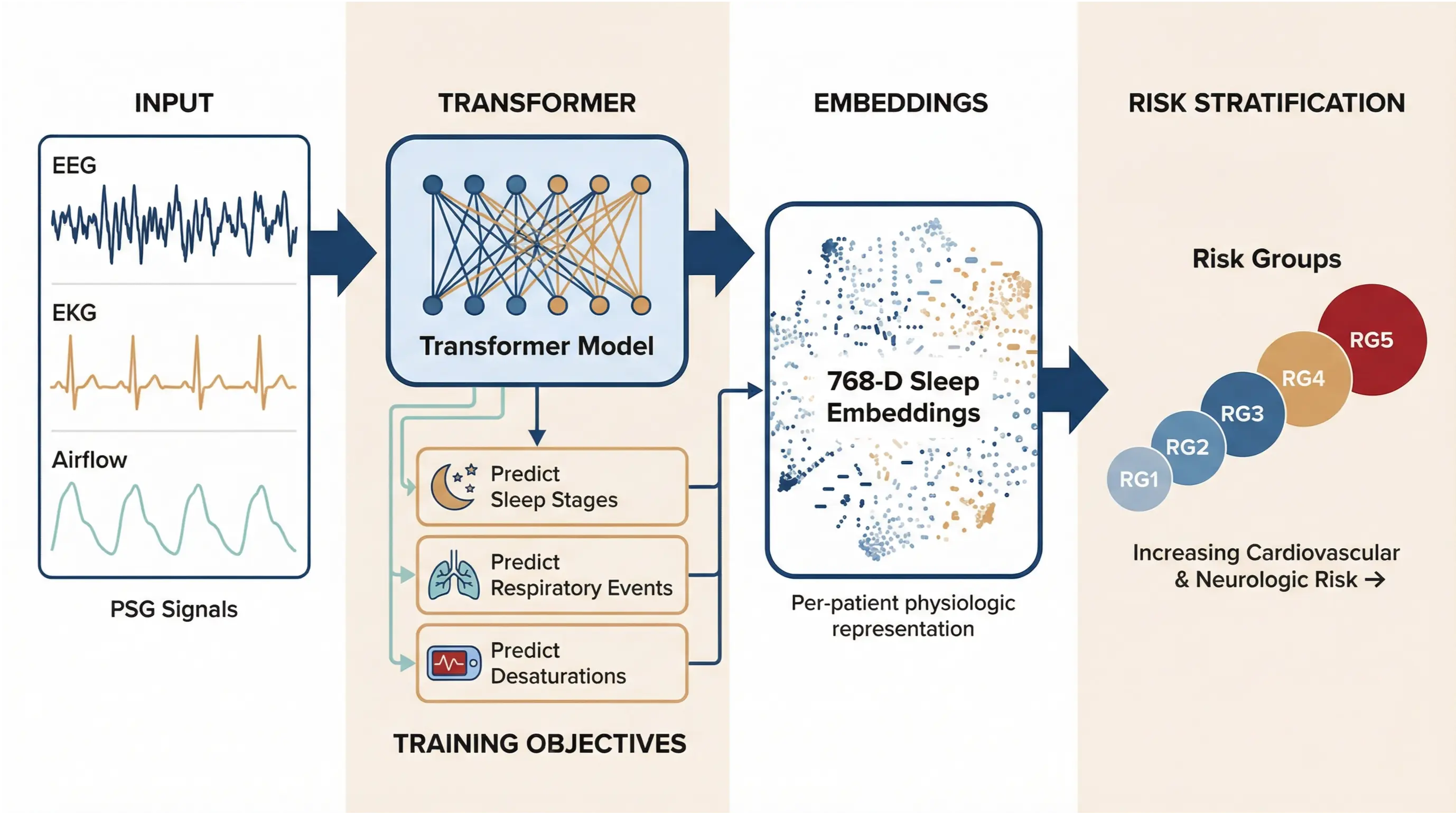

To break through this ceiling, we developed the first large-scale AI foundation model for sleep medicine. Using the STARLIT-10K dataset from the Cleveland Clinic, we trained a transformer-based model on over 10,000 in-laboratory polysomnography (PSG) studies linked to decades of electronic medical records.

How it Works:

Our model uses a multimodal approach that transforms raw PSG signals into rich physiologic representations. The transformer-based architecture is trained on three complementary objectives: predicting sleep stages, respiratory events (abnormal breathing such as apneas and hypopneas), and oxygen desaturations (drops in blood oxygen levels during sleep).

By learning these objectives jointly, the model is encouraged to capture the interplay between neural activity, breathing patterns, and oxygen regulation, rather than treating each signal in isolation. This multi-task learning setup biases the representation toward shared physiologic structure that reflects how disruptions in one system propagate across others over time.

The model generates 768-dimensional embeddings for each 30-second epoch of sleep, producing a high-resolution, matrix-like representation of an entire night rather than a single summary score. These embeddings capture substantially more physiologic information than traditional metrics such as AHI.

By aggregating and clustering these time-resolved representations, we identified five distinct patient risk groups (RG1–RG5) with markedly different cardiovascular and neurological risk profiles—patterns that are not apparent from conventional sleep measures alone.

The complete foundation model pipeline. Multimodal PSG signals (EEG, EKG, airflow) are processed by a transformer model trained on three objectives: predicting clinical outcomes, reconstructing signals, and contrastive learning. The model generates 768-dimensional sleep embeddings that capture each patient's unique physiologic signature. These embeddings are then clustered into five risk groups (RG1–RG5) with increasing cardiovascular and neurologic risk.

The complete foundation model pipeline. Multimodal PSG signals (EEG, EKG, airflow) are processed by a transformer model trained on three objectives: predicting clinical outcomes, reconstructing signals, and contrastive learning. The model generates 768-dimensional sleep embeddings that capture each patient's unique physiologic signature. These embeddings are then clustered into five risk groups (RG1–RG5) with increasing cardiovascular and neurologic risk.

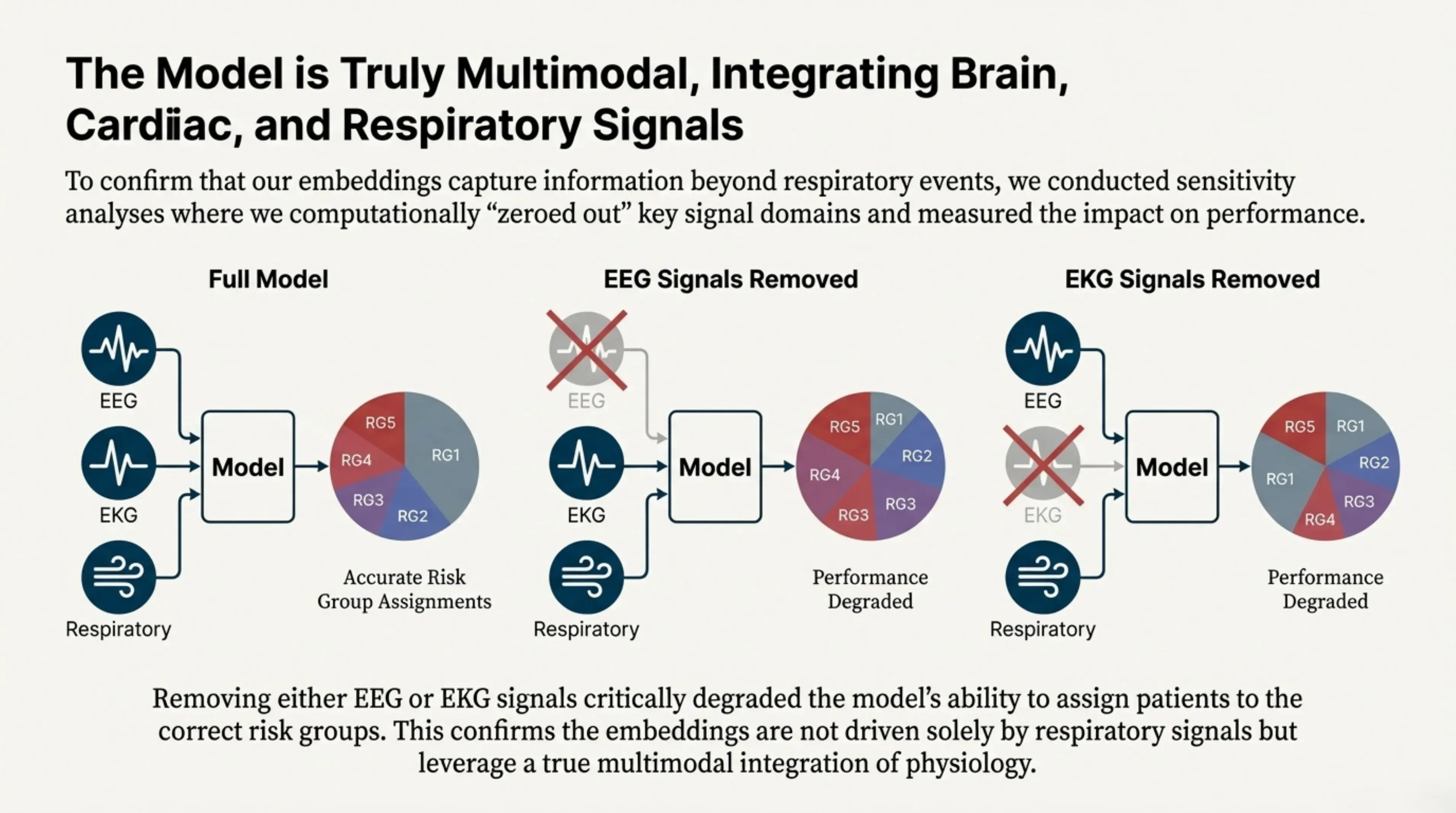

To confirm that the learned embeddings capture more than respiratory information alone, we performed sensitivity analyses in which specific signal domains were computationally removed and the impact on performance was measured. When either brain signals (EEG) or cardiac signals (EKG) were excluded, the model’s ability to correctly assign patients to risk groups degraded substantially. This demonstrates that the embeddings rely on a genuinely multimodal integration of physiology rather than being driven solely by respiratory events.

The model is truly multimodal, integrating brain (EEG), cardiac (EKG), and respiratory signals. Sensitivity analyses confirmed that removing either EEG or EKG signals critically degraded the model's ability to assign patients to the correct risk groups.

The model is truly multimodal, integrating brain (EEG), cardiac (EKG), and respiratory signals. Sensitivity analyses confirmed that removing either EEG or EKG signals critically degraded the model's ability to assign patients to the correct risk groups.

Discovering New Risk Groups

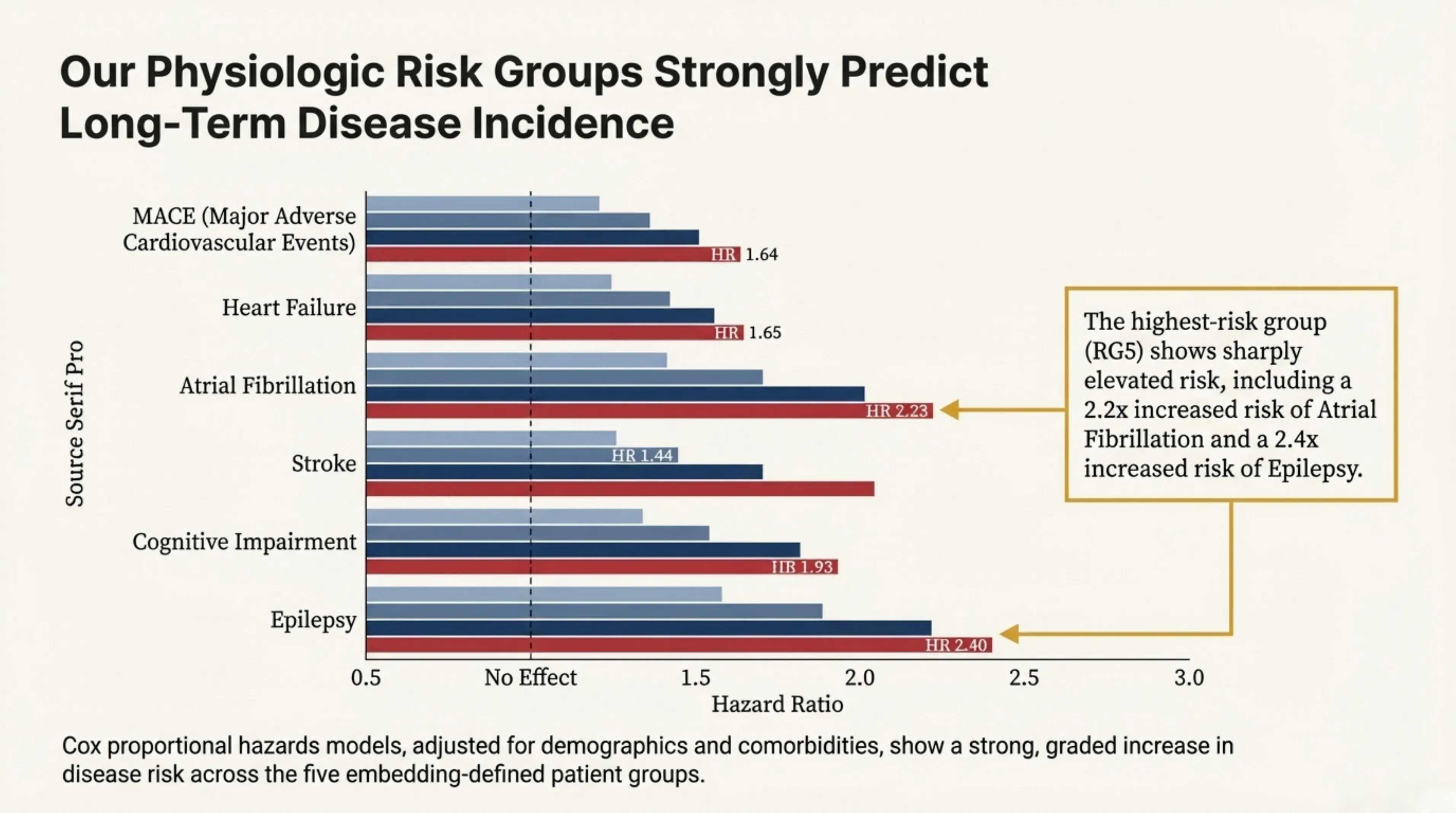

By clustering these physiologic embeddings, we identified five distinct patient risk groups (RG1–RG5) that are not captured by traditional sleep metrics. These groups strongly predict long-term disease incidence. In particular, the highest-risk group (RG5) exhibits sharply elevated risk, including a 2.2× increased risk of atrial fibrillation and a 2.4× increased risk of epilepsy.

Our physiologic risk groups strongly predict long-term disease incidence. The highest-risk group (RG5) shows sharply elevated risk, including a 2.2x increased risk of atrial fibrillation and a 2.4x increased risk of epilepsy.

Our physiologic risk groups strongly predict long-term disease incidence. The highest-risk group (RG5) shows sharply elevated risk, including a 2.2x increased risk of atrial fibrillation and a 2.4x increased risk of epilepsy.

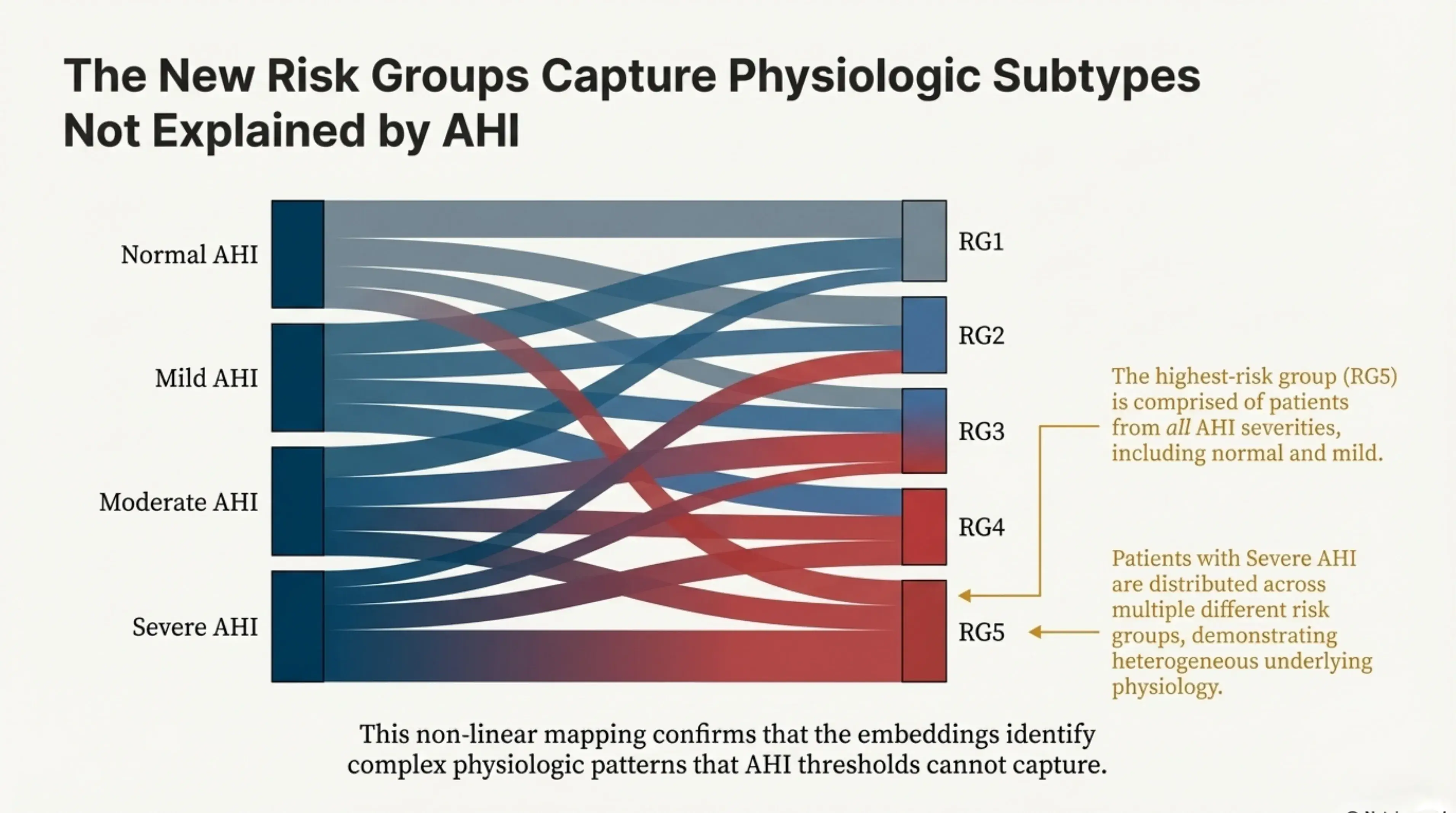

Interestingly, patients in the highest-risk group are distributed across the full range of AHI severities. Many individuals labeled as having “mild” sleep apnea fall into the most physiologically high-risk cluster, while some patients classified as “severe” by AHI appear in lower-risk groups. This non-linear relationship highlights how the learned embeddings capture complex physiologic patterns that fixed AHI thresholds fail to reflect.

This diagram visualizes the complex, non-linear mapping between traditional AHI and our AI-derived risk groups, proving that embeddings capture risks AHI cannot. The highest-risk group (RG5) is comprised of patients from all AHI severities, including normal and mild.

This diagram visualizes the complex, non-linear mapping between traditional AHI and our AI-derived risk groups, proving that embeddings capture risks AHI cannot. The highest-risk group (RG5) is comprised of patients from all AHI severities, including normal and mild.

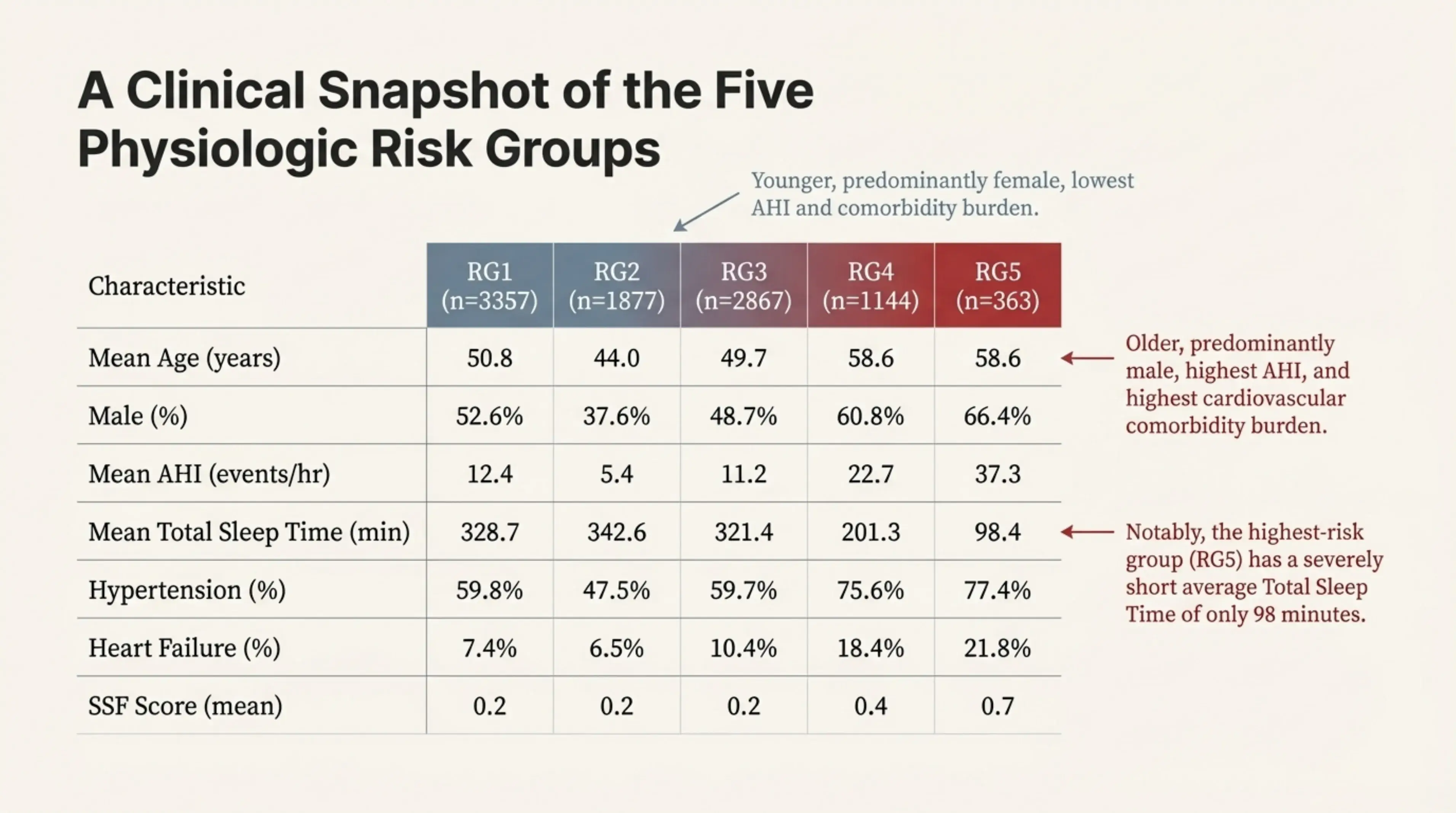

A closer look at the five physiologic risk groups reveals striking differences in overall sleep health. The highest-risk group (RG5) stands out with profoundly disrupted sleep, including an average total sleep time of just over 90 minutes per night—far below what is considered restorative. This group also shows higher AHI values and a greater burden of cardiovascular comorbidities, and is composed of older, predominantly male patients.

Crucially, these demographic and clinical factors do not fully explain the elevated risk. Even after accounting for age, sex, and existing comorbidities, membership in this group remains strongly associated with adverse outcomes. This indicates that the elevated risk is driven by underlying physiologic patterns captured by the embeddings, rather than by traditional risk factors alone.

A clinical snapshot of the five physiologic risk groups. Notably, the highest-risk group (RG5) has a severely short average total sleep time of only 98 minutes, along with the highest AHI and cardiovascular comorbidity burden.

A clinical snapshot of the five physiologic risk groups. Notably, the highest-risk group (RG5) has a severely short average total sleep time of only 98 minutes, along with the highest AHI and cardiovascular comorbidity burden.

Validation and Generalizability

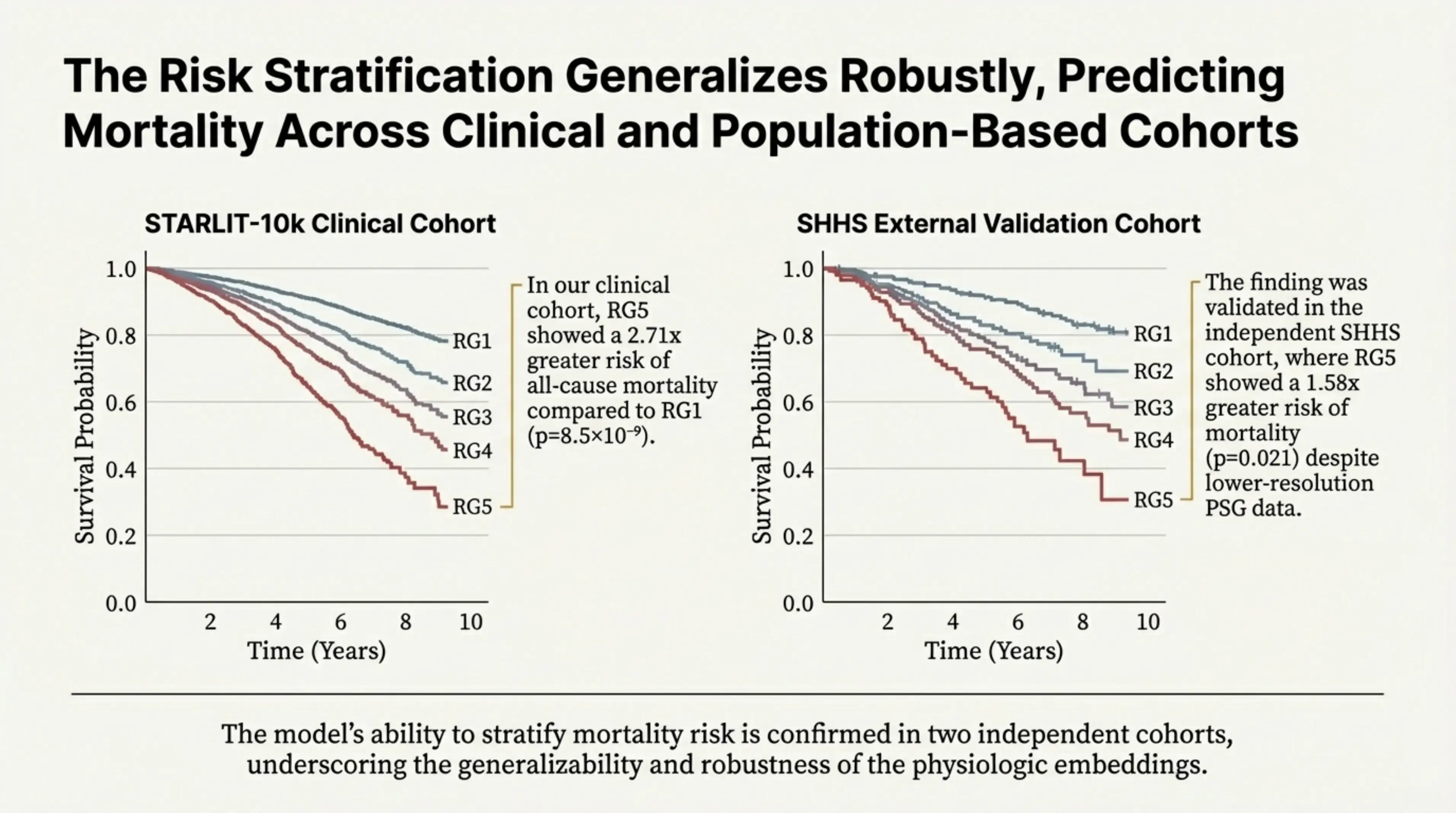

The model’s ability to stratify mortality risk was confirmed across two independent cohorts, highlighting both the robustness and generalizability of the learned physiologic embeddings. In STARLIT-10k, a real-world clinical cohort drawn from patients referred for sleep evaluation, individuals in the highest-risk group (RG5) exhibited a 2.71× greater risk of all-cause mortality compared to the lowest-risk group (RG1).

Importantly, this finding also held in a very different setting. When the same framework was applied to the Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS)—a large, population-based longitudinal study with lower-resolution sleep recordings—the highest-risk group still showed a 1.58× increased risk of mortality. The ability to reproduce the risk structure across both a clinical cohort and a general population study demonstrates that the embeddings capture fundamental physiologic patterns rather than cohort-specific artifacts.

The risk stratification generalizes robustly, predicting mortality across clinical and population-based cohorts. In our clinical cohort, RG5 showed a 2.71x greater risk of all-cause mortality compared to RG1. The finding was validated in the independent SHHS cohort, where RG5 showed a 1.58x greater risk of mortality despite lower-resolution PSG data.

The risk stratification generalizes robustly, predicting mortality across clinical and population-based cohorts. In our clinical cohort, RG5 showed a 2.71x greater risk of all-cause mortality compared to RG1. The finding was validated in the independent SHHS cohort, where RG5 showed a 1.58x greater risk of mortality despite lower-resolution PSG data.

Why This Matters for the Future of Healthcare

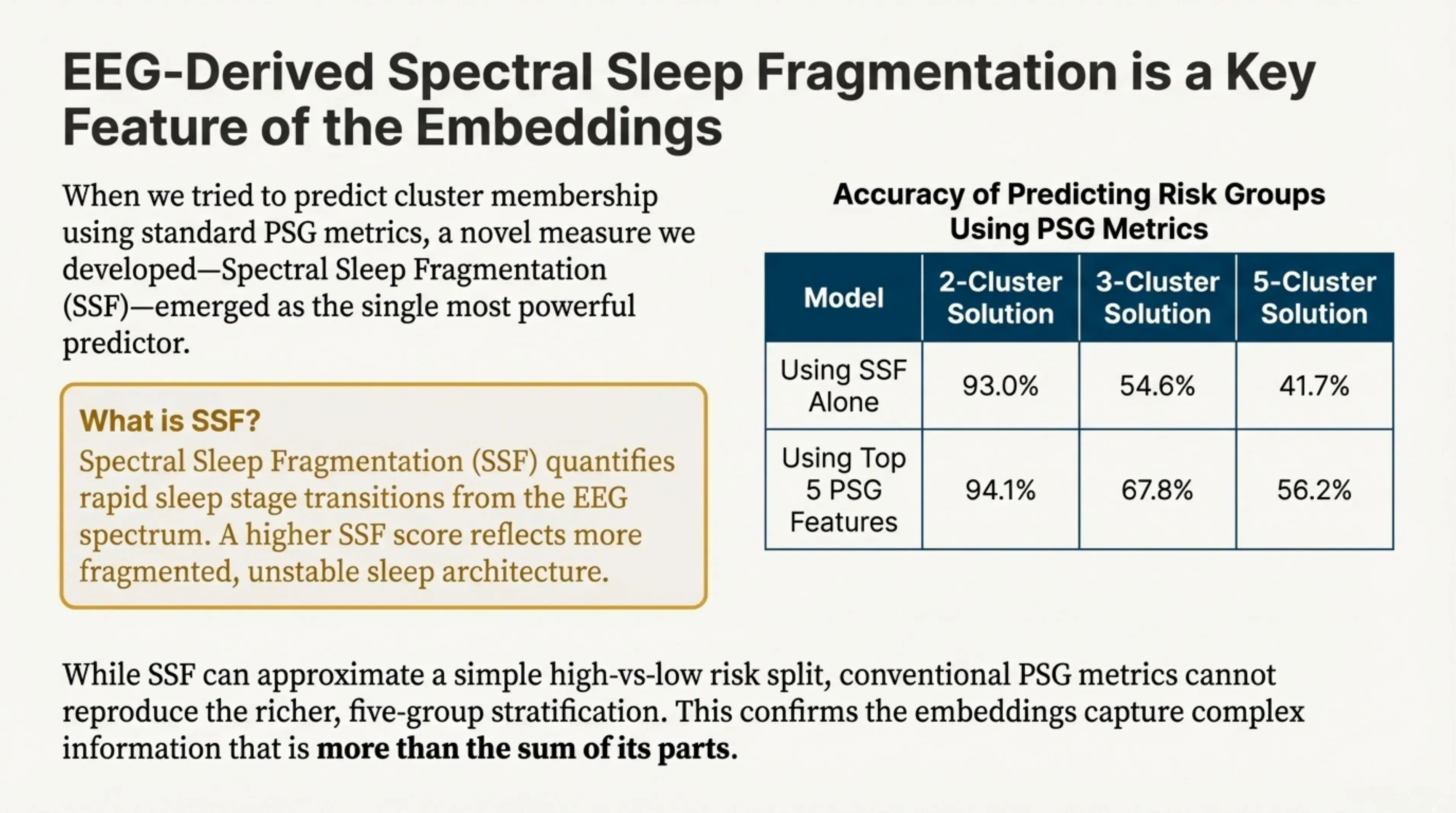

The implications for precision medicine are significant, but they also highlight an important limitation of conventional sleep metrics. We explicitly examined whether any interpretable, hand-crafted PSG measures could reproduce the embedding-derived patient groupings. With one partial exception, they could not.

Spectral Sleep Fragmentation (SSF)—a novel measure we developed and closely related to the traditional arousal index—emerged as the strongest single correlate of cluster structure. SSF quantifies rapid sleep-stage transitions directly from the EEG spectrum, with higher values reflecting more fragmented and unstable sleep architecture.

However, while SSF helps separate patients in a coarse, two-cluster setting, no existing PSG metric—or combination of metrics—was able to recover the full five-cluster solution discovered by the foundation model. This result underscores that the learned embeddings encode higher-order, multivariate physiological structure that is not captured by standard summary measures alone.

EEG-derived Spectral Sleep Fragmentation (SSF) is a key feature of the embeddings. SSF quantifies rapid sleep stage transitions from the EEG spectrum. A higher SSF score reflects more fragmented, unstable sleep architecture.

EEG-derived Spectral Sleep Fragmentation (SSF) is a key feature of the embeddings. SSF quantifies rapid sleep stage transitions from the EEG spectrum. A higher SSF score reflects more fragmented, unstable sleep architecture.

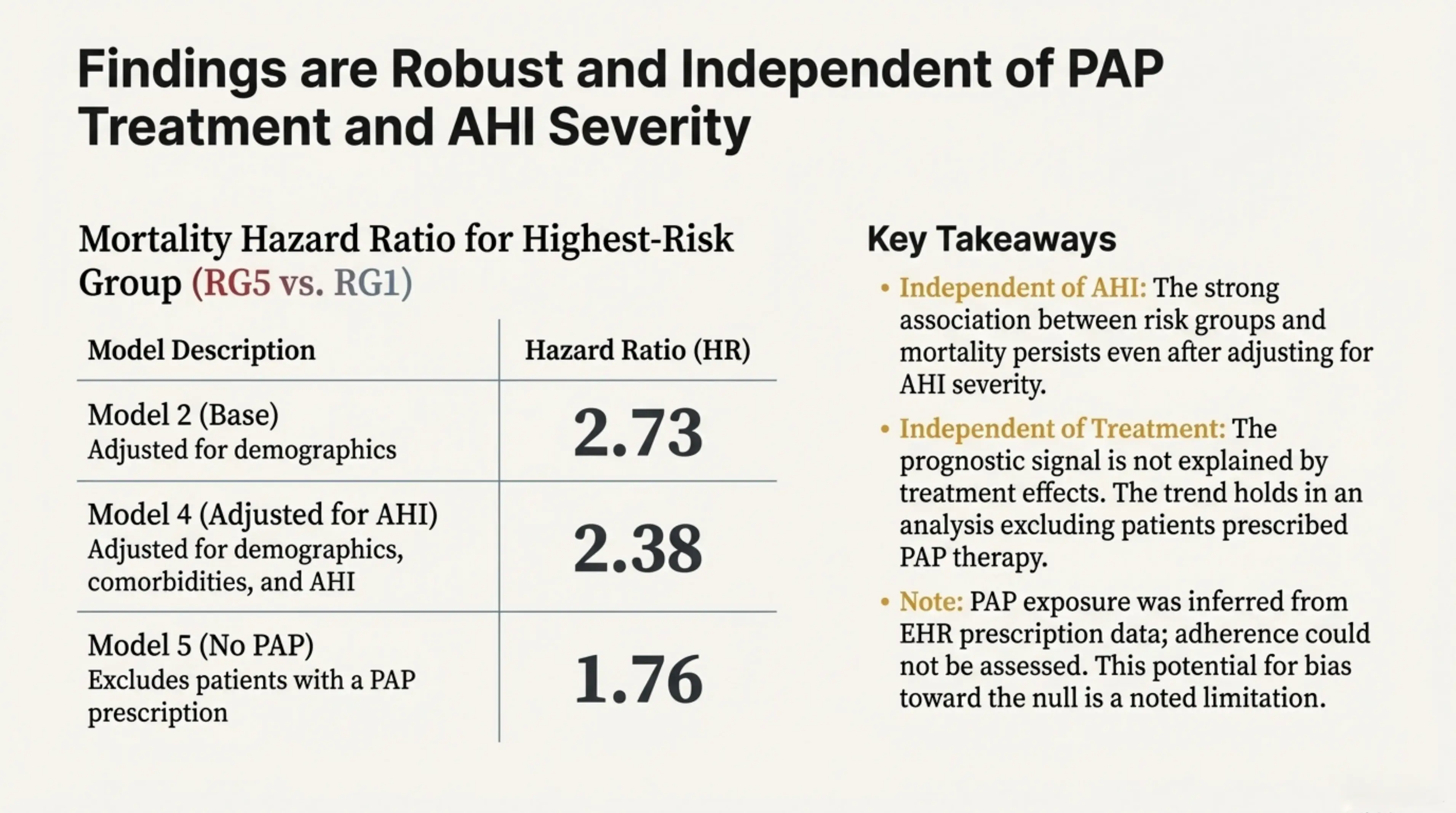

Importantly, these findings are robust and do not depend on PAP treatment or AHI severity. The strong association between our AI-derived risk groups and mortality persists even after accounting for AHI severity and after excluding patients who were prescribed PAP therapy. This suggests that the identified risk structure reflects underlying physiology rather than treatment effects or conventional severity categories.

Findings are robust and independent of PAP treatment and AHI severity. The strong association between risk groups and mortality persists even after adjusting for AHI severity and excluding patients prescribed PAP therapy.

Findings are robust and independent of PAP treatment and AHI severity. The strong association between risk groups and mortality persists even after adjusting for AHI severity and excluding patients prescribed PAP therapy.

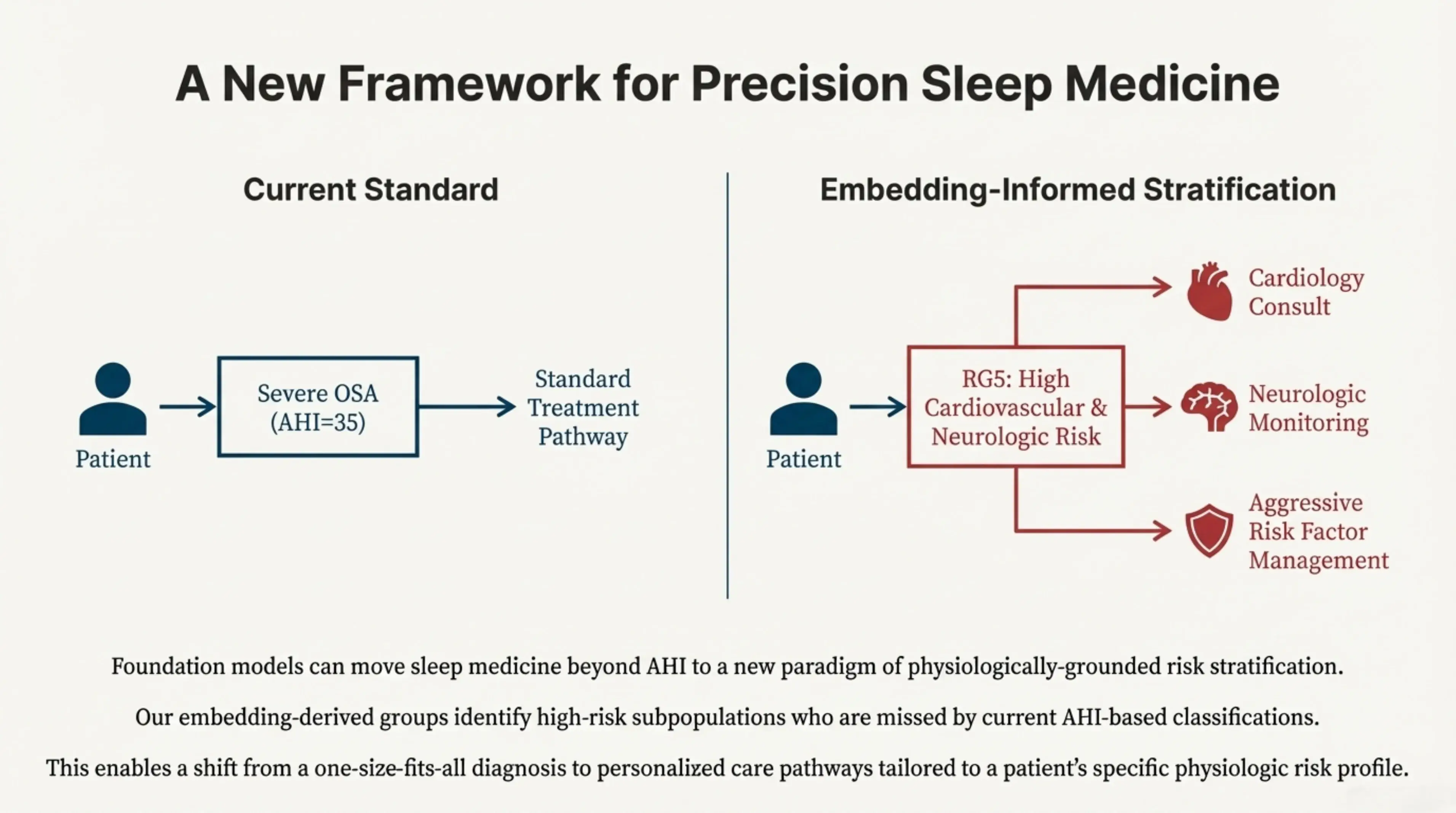

A New Framework for Precision Sleep Medicine

More broadly, this work illustrates how foundation models can move sleep medicine beyond AHI toward a framework grounded in physiology rather than thresholds. The embedding-derived risk groups reveal high-risk subpopulations that are systematically missed by current AHI-based classifications, enabling a shift from one-size-fits-all diagnosis to care pathways tailored to an individual patient’s physiologic risk profile.

Foundation models can move sleep medicine beyond AHI to a new paradigm of physiologically-grounded risk stratification. Our embedding-derived groups identify high-risk subpopulations who are missed by current AHI-based classifications. This enables a shift from a one-size-fits-all diagnosis to personalized care pathways tailored to a patient's specific physiologic risk profile.

Foundation models can move sleep medicine beyond AHI to a new paradigm of physiologically-grounded risk stratification. Our embedding-derived groups identify high-risk subpopulations who are missed by current AHI-based classifications. This enables a shift from a one-size-fits-all diagnosis to personalized care pathways tailored to a patient's specific physiologic risk profile.

Key Takeaways:

- Better Triage: We can identify high-risk patients who would otherwise be ignored because they have a low AHI.

- Personalized Care: Moving beyond a "one-size-fits-all" approach to sleep apnea treatment.

- Scalability: Foundation models allow us to extract these markers from routine PSG data without needing manual, hand-crafted features.

This work establishes a scalable foundation for embedding-based risk stratification, providing a robust new tool to guide monitoring, referral, and intervention in precision sleep medicine.

At Hogarthian Technologies, we apply this same foundation-model mindset to a different class of problems: building voice agents that must operate in noisy, real-world environments where simple rules and single metrics break down quickly.

Today, that means reliable AI agents that can answer calls, take orders, and administer surveys. Over time, it extends toward automating onboarding, managing agent lifecycles, and ultimately serving as an operational layer for an AI workforce.

This paper reflects the intellectual roots of that approach. It is not the destination—but it clearly points the way forward.

To read the full study and explore the data, visit the pre-print version at PubMed.